In medieval England, the crown promised authority but delivered uncertainty. Kings were crowned with sacred oil, hailed by the Church, and acknowledged by noble assemblies, yet few ruled without opposition. Many spent their reigns defending their position against rivals, rebellious nobles, or the quiet withdrawal of loyalty that proved just as dangerous. To be king was not to command unquestioned obedience; it was to survive within a system that allowed — and at times encouraged — resistance.

The popular image of medieval monarchy suggests absolute power: a king whose word was law and whose authority flowed directly from God. The reality was far more fragile. English kingship rested on shifting foundations of bloodline, political consent, military success, and moral authority. When one failed, the entire structure weakened. Failure was not unusual; it was part of the system.

This article explores why kingship in medieval England was so unstable, how legitimacy truly worked, and why royal authority was often limited, contested, or symbolic. Rather than treating medieval kings as distant icons, it examines kingship as it was lived — uncertain, negotiated, and frequently tested.

What Did It Mean to Be a King in Medieval England?

To understand medieval English kingship, we must first abandon modern assumptions about power. A king was expected to rule, but his ability to do so depended heavily on others. He led armies, presided over justice, defended the Church, and maintained order, yet none of these roles guaranteed obedience.

England developed with a powerful aristocracy. Great lords controlled vast estates, administered justice locally, and commanded their own armed followers. Kings relied on them for military campaigns, taxation, and governance. This reliance meant authority was shared rather than imposed. Royal power functioned through cooperation, not command.

A successful king was one who balanced competing interests: rewarding loyalty without encouraging independence, enforcing authority without provoking resistance, and maintaining prestige without exhausting resources. When that balance failed, so did the king’s authority.

As explored more deeply in What Made a King Legitimate in Medieval England, kingship was not a fixed status. It was a role that required constant reinforcement.

Legitimacy: More Than a Crown and a Coronation

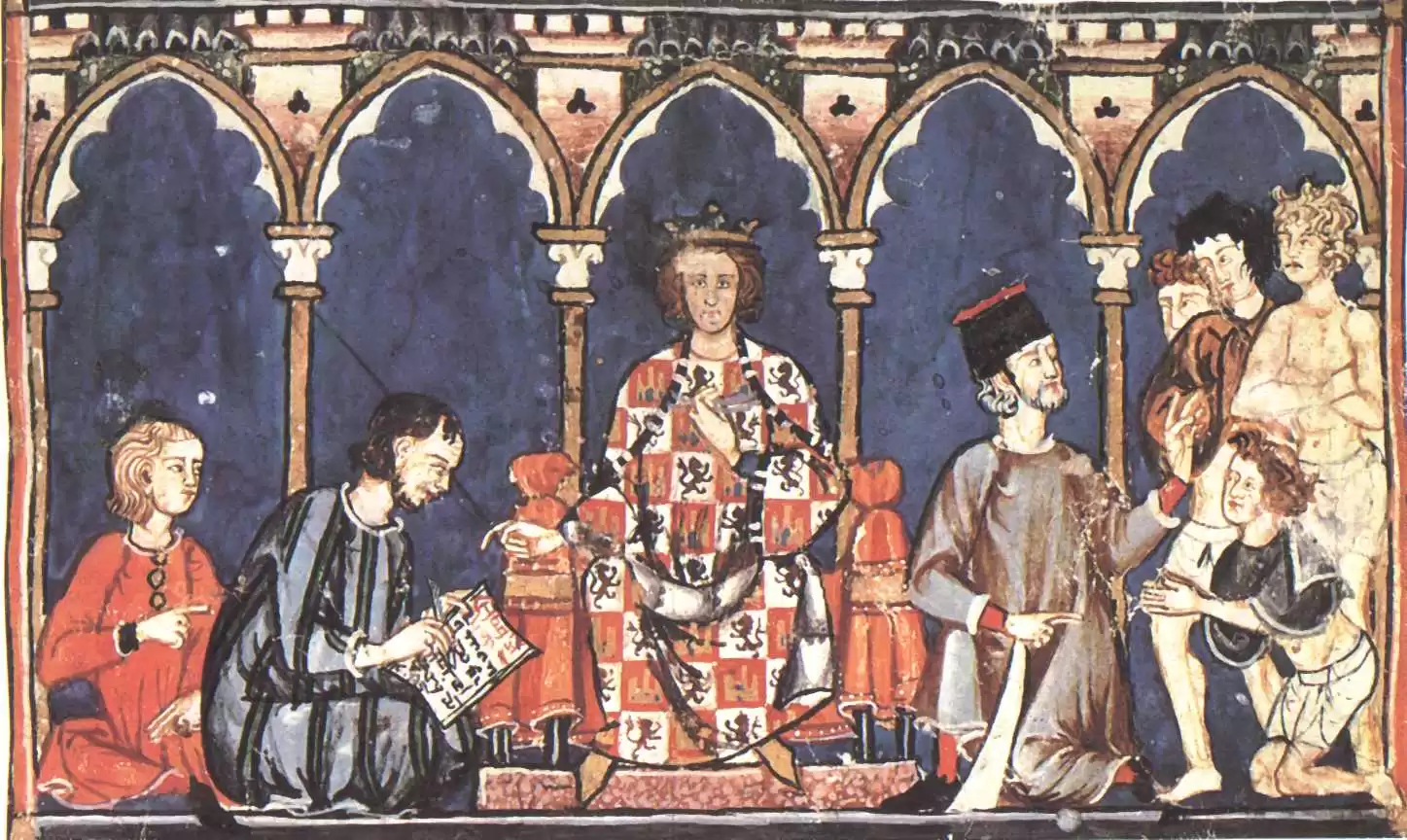

Legitimacy lay at the heart of medieval rule. A king needed to be seen as rightful — by nobles, by the Church, and by the wider political community. Coronation was important, but it was only the beginning.

Royal legitimacy rested on three main pillars:

- Hereditary claim – descent from a recognised royal line

- Political acceptance – support from leading nobles and officials

- Spiritual approval – recognition by the Church

If any of these were weak, authority suffered. A king with a strong bloodline but little noble support struggled to govern. A politically capable king who clashed with the Church risked spiritual isolation. Legitimacy was fragile and reversible.

This conditional nature of authority explains why medieval English kings were so often challenged. The crown did not silence opposition; it invited scrutiny.

Royal Blood and the Illusion of Security

Medieval society believed deeply in the power of lineage. Royal blood was thought to carry divine favour, yet English history repeatedly shows that birth alone did not guarantee loyalty.

Succession was rarely straightforward. Brothers, cousins, and distant relatives advanced competing claims. Illegitimate children were sometimes favoured over lawful heirs. Child kings inherited thrones they could not defend, leaving power in the hands of regents and ambitious nobles.

Royal birth could even be dangerous. A weak king with a strong claim encouraged rivals who believed they could rule better. This tension between inheritance and obedience is explored further in Why Royal Birth Did Not Guarantee Obedience.

In England, blood granted a claim — not safety.

Hereditary Right Versus Political Reality

The conflict between hereditary right and political acceptance shaped much of medieval English history, particularly during the Angevin period. Kings inherited vast territories through blood, yet struggled to command loyalty at home.

Noble consent mattered more than genealogy. Councils, assemblies, and informal alliances determined whether a king could rule effectively. A monarch without noble backing was vulnerable, regardless of ancestry.

This struggle explains why kings with impeccable lineage could fail, while others with weaker claims succeeded through political skill. The English throne belonged not to the most legitimate heir, but to the most accepted ruler — a theme examined in Hereditary Right vs Political Acceptance in Angevin Rule.

A Throne Under Constant Threat

English kings were rarely secure. Rebellion was not exceptional — it was part of political life. Powerful nobles maintained private armies and strong regional influence. When royal authority weakened, resistance followed quickly.

Financial pressures added to instability. Kings needed funds for war, administration, and patronage, yet taxation required consent. Excessive demands provoked rebellion; insufficient demands signalled weakness. There was no safe balance.

Military success mattered deeply. Defeat damaged prestige, and prestige was central to authority. A king who lost battles lost respect, and once respect vanished, loyalty followed.

This persistent insecurity is explored fully in Why English Kings Were Never Secure on the Throne, where instability is shown to be structural rather than accidental.

The Fragility of Authority in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries

The twelfth and thirteenth centuries highlight how constrained English kingship had become. Government expanded through courts, officials, and written law, but this often limited the king rather than empowering him.

Kings who ruled territories abroad faced particular difficulty. Long absences weakened control in England, allowing nobles to strengthen independent power bases. Authority required presence, and absence bred opposition.

Law also imposed limits. Kings were increasingly expected to rule according to custom and precedent. Actions seen as unjust or arbitrary invited resistance. Authority existed, but it operated within accepted boundaries.

As shown in The Fragility of Royal Authority in the 12th–13th Centuries, medieval kings ruled not above the system, but within it.

Weak Kings and the Growth of Noble Resistance

Weakness was the greatest danger to medieval kingship. A weak king failed to lead armies effectively, reward loyalty, or control finances. Such failures encouraged opposition.

Nobles rarely described themselves as rebels. Instead, they framed resistance as defence of tradition and good governance. Rebellion became a moral argument rather than a criminal act.

Through councils, forced agreements, and imposed limitations, nobles reshaped royal authority. Kings remained crowned, but increasingly constrained. This process is examined in How Weak Kings Invited Noble Resistance.

Resistance was not a breakdown of order — it was part of how order functioned.

Queens, Consorts, and the Hidden Politics of Legitimacy

Queens played a crucial yet understated role in medieval kingship. Through marriage, they created alliances. Through motherhood, they secured succession. Through regency, they governed during minorities or absences.

Public perception mattered. A respected queen strengthened royal legitimacy; an unpopular one undermined it. Queens influenced how kingship was viewed and accepted, even when they ruled indirectly.

Their importance is explored in Queens, Consorts, and the Politics of Legitimacy, which shows that authority was not only legal or military — it was social.

The Church: Sacred Authority and Political Constraint

The Church crowned kings and declared them God’s anointed rulers. Yet sacred authority came with expectations. Kings were expected to govern justly and respect ecclesiastical power.

Excommunication was a powerful weapon. A king cut off from the Church lost moral authority and encouraged rebellion. Spiritual isolation weakened political control.

The Church elevated kingship while limiting it. This complex relationship is explored further in The Role of the Church in Defining Kingship.

Kings Who Ruled in Name Only

There were times when English kings wore the crown but lacked real authority. Child kings ruled through regents. Councils dictated policy. Powerful nobles governed behind the scenes.

Yet monarchy endured. Kingship adapted rather than collapsed. Authority became negotiated and shared. These periods are explored in When English Kings Ruled in Name Only.

Conclusion: Kingship as a Test, Not a Right

Medieval English kingship was never guaranteed. Authority depended on acceptance, competence, and circumstance. Kings ruled only so long as others believed they should.

Failure was common because the system encouraged challenge. Yet from this instability emerged lasting ideas: limits on power, shared governance, and accountability.

The crown endured not because it was absolute, but because it survived weakness. In medieval England, kingship was not a reward for birth — it was a trial, and many failed it.